A Word (or Two) About Boro and Sashiko

Aug 17th 2022

Excerpted from Boro & Sashiko, Harmonious Imperfection by Shannon Leigh Roudhán and Jason Bowlsby. Copyright © 2020 by C&T Publishing. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

A Word (or Two) About Boro and Sashiko

Sashiko: The “Little Stabs”

If we are going to talk about boro, we have to include sashiko in the conversation. Because, while sashiko can exist without boro, boro cannot exist without sashiko—the stitches that hold the boro patches in place.

Literally translated, sashiko means “little stabs,” and that is exactly what it is. Sashiko refers to the small running stitches that were used to attach the boro patches to the garment and to strengthen weak fabrics or areas of intense wear. These stitches could be sewn in straight lines, symbols, motifs, pictures, or without thought as to how they appeared. The ultimate goal of sashiko was to secure, strengthen, and embellish.

Constructed of rough plant fibers and woven on rustic looms, the cloth of the working classes was loosely woven. The addition of white ramie thread would in no small manner reweave the fabric, which helped close up the holes in the base cloth, and also secure additional layers of fabric, which added warmth in a harsh climate. For these farmers and fishers, the main purpose of boro and sashiko was to make cloth thicker, warmer, and more durable.

Now we can look back at sashiko through the lens of time and with socio-political distance, and we can see the beauty and even the art of this utilitarian practice. The main religion of Japan was Shinto Buddhism, in which every natural element, object, person, plant, and animal is imbued with kami, or spirit. Representing a natural element, plant, or object in stitching transferred the powers and properties of those elements and objects to the wearer, as in the examples that follow.

Asanoha, the hemp leaf sashiko pattern, represents good fortune, good health, and growth.

Yamagata, a mountain form sashiko pattern, gifts the wearer with strength and steadfastness.

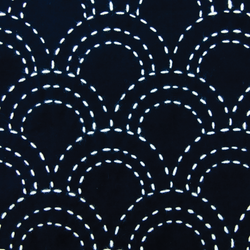

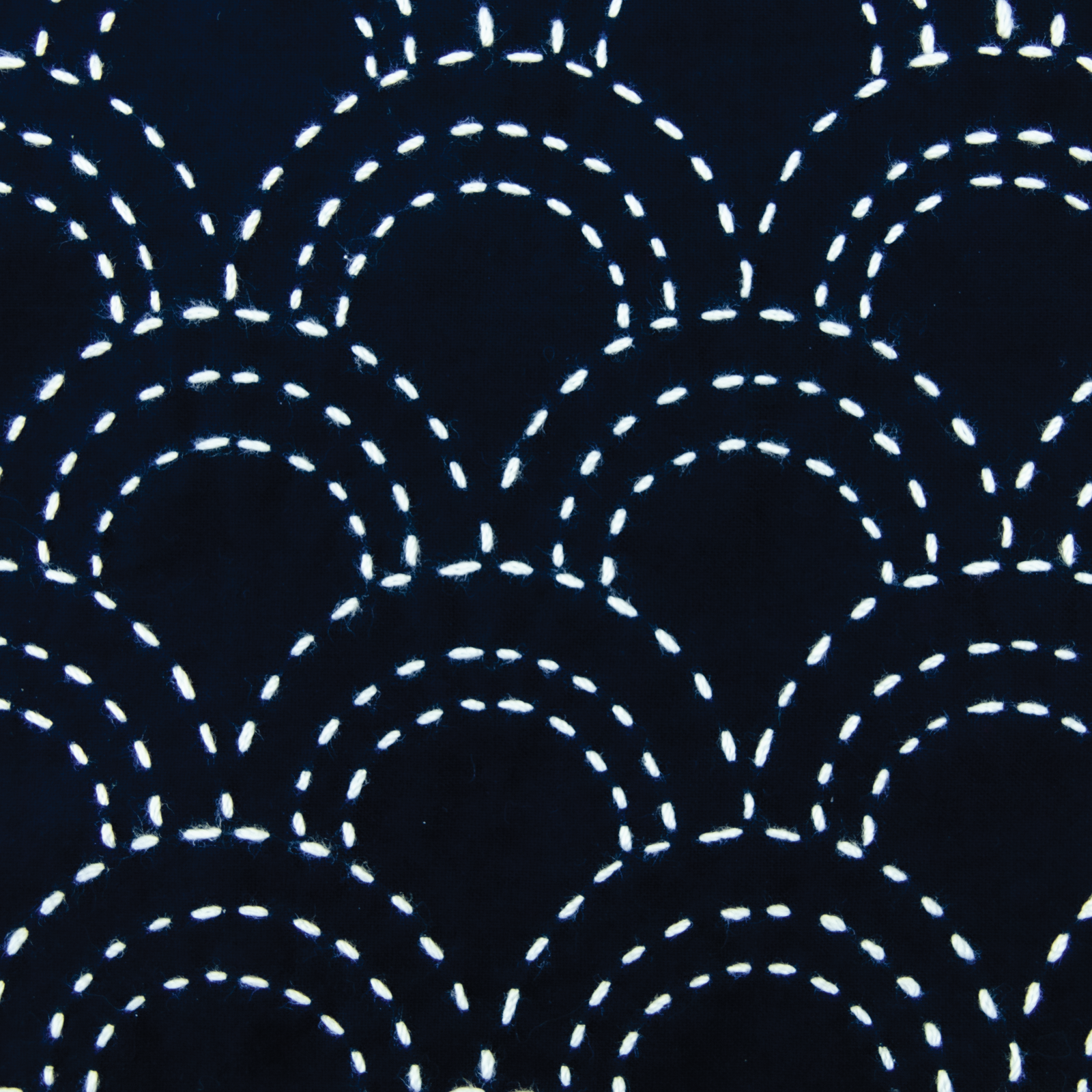

Seigaiha, a waves sashiko pattern, produces the effect of resilience, tranquility, and the ability to literally “go with the flow.”

Although there are regional variations to each, sashiko can be grouped into three main forms:

HITOMEZASHI SASHIKO

Hitomezashi- style sashiko is based on a grid with patterns developing from intersecting and crossing lines of stitches.

113

An example of hitomezashi sashiko worked over a kimono, from the Seattle Art Museum’s Asian art collection

MOYOUZASHI SASHIKO

Moyouzashi-style sashiko patterns are based on simple straight or curved lines using as many stitches as needed to get from one point to another. Stitches may be counted, but lines of moyouzashi stitches never cross on the front of the fabric.

An example of moyouzashi sashiko, showing the curved lines following pre-drawn shapes, from the Seattle Art Museum’s Asian art collection

KOGIN-ZASHI

Kogin means “small cloth” and zashi means “stitches.” Kogin is a form of counted embroidery, in which elaborate designs of geometric patterns are created by counting the number of threads in the base fabric that are sewn over or under. It is worked one row at a time using the warp and weft threads to create a grid upon which the Kogin motifs are built.

Kogin patterns are made up of smaller elements called modoko. These modoko are combined to make larger, complex motifs and overall fabric patterns that are the defining characteristic of Kogin-zashi. Kogin is a study in and of itself with an entire agency—the Hirosaki Kogin Research Institute—dedicated solely to the research and preservation of this particular sashiko technique.

Shannon practicing Kogin-zashi sashiko, used to fill the spaces of loosely woven fabric

Regardless of style, sashiko stitch patterns are made using the running stitch. Further, they are created by loading the fabric onto the needle and creating many stitches (sometimes an entire row) at one time. The fabric is loaded onto the needle, then pushed through the fabric using a palm thimble. The fabric then is pulled all at once along the length of the thread and smoothed out, ensuring that the thread is neither puckering the fabric nor that is it too loose.

All sashiko stitches are made without a hoop, with the fabric and thread tension maintained entirely by hand. This does take a bit of practice but, once you have achieved the dexterity and rhythm, it is relaxing and even meditative.

Throughout this book we will be using a combination of hitomezashi and moyouzashi stitches to secure our boro patches, strengthen the fabrics, and embellish the projects.

Shop Boro & Sashiko, Harmonious Imperfection

WANT MORE CREATIVE CONTENT? SIGN UP AND RECEIVE 30% OFF YOUR FIRST ORDER.